Quick summary

PDFs, Word documents, PowerPoints, and Excel spreadsheets are non-HTML documents.

Non-HTML documents have special accessibility considerations. Making these documents accessible is usually extra work than making an HTML webpage accessible, which is why we suggest using HTML webpages whenever possible.

Rather watch the video? Watch Inaccessible PDF read with screen reader example video to learn what makes PDFs accessible and listen to a PDF read with a screen reader.

Visit May Accessibility Focus: PDFs, non-HTML documents for more articles and video resources or learn How to check and fix PDF accessibility issues.

What are PDF and non-HTML documents?

When navigating the web, you’ve probably come across links to or embeds of documents. They can be PDFs, Word docs, Excel sheets, PowerPoints, or other document types.

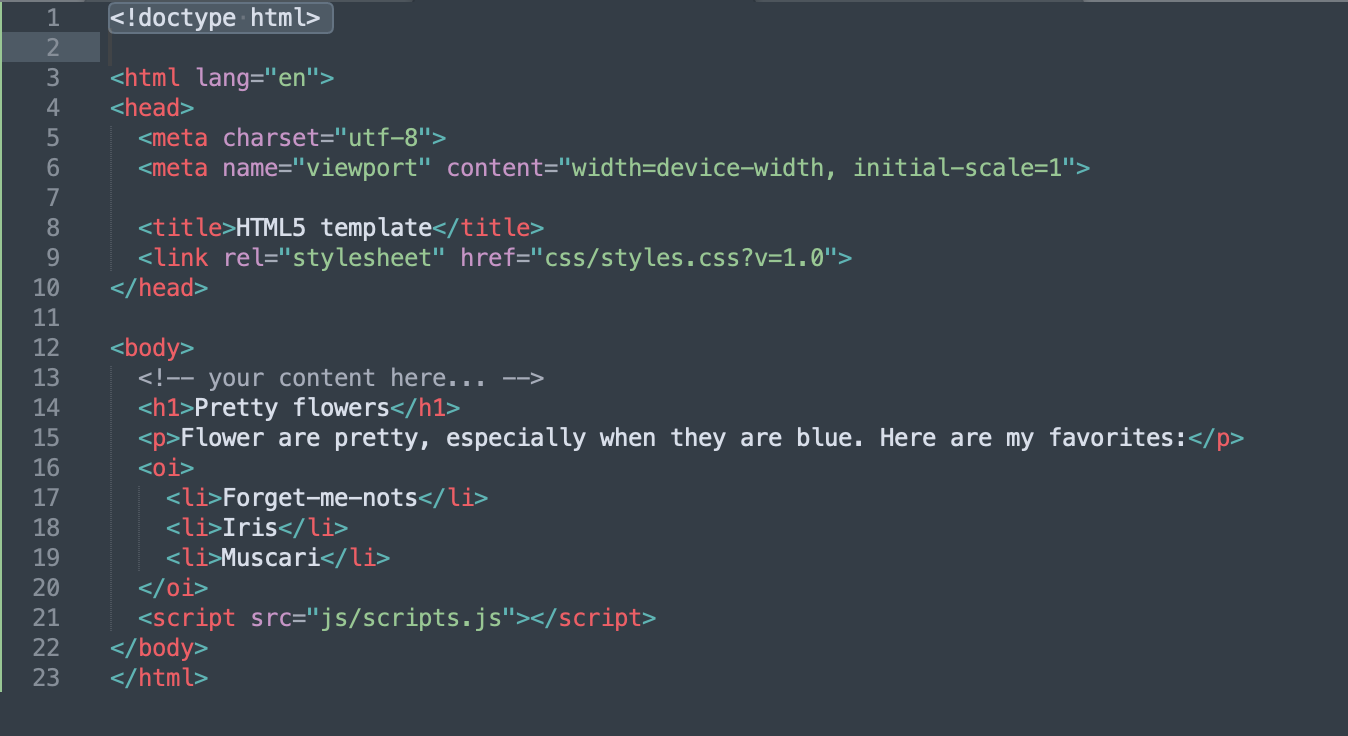

Non-HTML documents are made without using HTML, so they don’t have the underlying HTML code webpages have.

How do inaccessible documents affect an assistive technology user’s experience?

Inaccessible documents can make it so people using assistive technology can’t navigate or, sometimes, can’t even read the content of the document.

Let’s get right into what makes the different document types inaccessible and accessible.

PDFs

Most PDFs on the web are inaccessible. In WebAIM’s 2019 screen reader user survey, 75% of respondents said they were very or somewhat likely to have significant accessibility issues with a PDF.

An extreme, but common, example of inaccessible PDFs are ones with scanned images of text. Since the text is an image, the screen reader literally has nothing to read.

Another example are PDFs with text, but they aren’t tagged properly. These can still be difficult for assistive technologies to read and navigate.

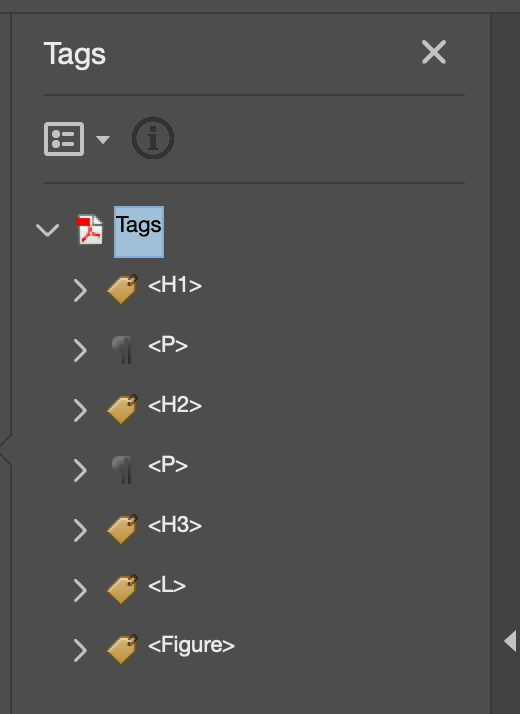

PDFs must be tagged to be accessible. Like HTML code, tagging defines what content is a heading, list, body text, image, etc. Tagging is hidden unless being used by an assistive technology. The image below shows what the Tags pane looks like in Adobe Acrobat.

The other part to an accessible PDF is its reading order. This is the order the document is read by a screen reader. Both the tag and content order need to be checked so the PDF makes sense when read by a screen reader.

The reading order can also affect how a PDF shows up on a mobile device. If the order is wrong, paragraphs, images, and headings could show in the wrong order.

On top of tagging and reading order, PDFs still need common accessibility strategies like alternative text on images, high contrast for colors, table headings and captions, and descriptive form labels.

Word docs, PowerPoints, and Excel sheets

Several of the same accessibility best practices for HTML content are used to make accessible Word docs, PowerPoints, and Excel sheets. That includes:

- Alternative text on images

- High enough contrast for text, images, and graphics

- Proper heading hierarchy

- Descriptive links

- Only use tables to display data

Some specific ways to make PowerPoints accessible are:

- Check reading order for PowerPoint slides.

- Give every PowerPoint slide a unique title.

- Make sure any videos in your PowerPoint are accessible.

These are specific ways to help make your Excel sheets accessible:

- Add text to the A1 cell in Excel sheets. Screen readers will always start reading A1.

- Give all worksheets unique names and remove blank ones.

Why you should identify the document type in the link

Another way to help assistive technology users is to identify the document type when you link to a document. This helps because it gives an assistive technology user a warning that it isn’t an HTML page, so they know to expect a download or a PDF.

Here are three examples of how you could write a link with the document in it:

- PDF purge planning sheet (Excel)

- Syllabus (PDF)

- Lecture 1 PowerPoint presentation

What are alternatives to PDF documents?

Since making PDFs accessible takes additional steps like tagging and checking the reading order on top of the other accessibility considerations, most PDFs end up not being accessible.

HTML

Instead, we suggest creating PDF documents as HTML web pages whenever possible. As long as the HTML web page is built with accessibility in mind, it doesn’t require additional steps to work with assistive technology. For example, HTML documents have tagging and reading order automatically embedded in them.

Visit Inaccessible PDFs? How to know when to use HTML webpages instead of PDFs to learn the six pros of HTML, when to use PDFs, and the thought process behind choosing a PDF or HTML webpage.

Word

Another alternative is Word documents. In 2021, WebAIM surveyed screen reader users and found that 68.9% thought Word docs were more accessible. Only 12.9% of respondents thought PDFs were the most accessible documents.

How do I determine if documents are accessible?

The best way to determine if a document is accessible is to use a screen reader to test it.

You can also use Adobe Acrobat Pro to check and fix PDF accessibility issues.

Here are two free screen reader tools you could use:

Watch these videos for an introduction to screen reader testing PDFs:

Key takeaways

- PDF and non-HTML documents are linked to or embedded in web pages. They can include PDFs, Word docs, Excel sheets, or PowerPoints.

- To make PDFs accessible, tag them and check their reading order.

- All documents still need accessibility applied through alt text, high contrast between colors, proper heading structure, descriptive links, tables that are used for data, and other accessible design techniques.

- When linking to a document, include the document type in the link. For example, Syllabus (PDF).

- Since making PDFs accessible takes additional steps and time, most PDFs are inaccessible. As an alternative, create an HTML web page instead.

- Use screen reader tools like Mac’s VoiceOver or Window’s NVDA to check if your documents are accessible.

Common questions

When should I use a PDF instead of HTML?

In general, HTML is easier for people to use and most PDFs could be HTML web pages. There are some situations where a PDF could be better:

- When the format needs to be exact, like a floor plan.

- Content that needs to be saved offline.

- Documents that are meant for printing.

How much does it cost to fix an inaccessible PDF?

The cost to fix an inaccessible PDF varies based on the size and complexity of the PDF. For example, a PDF with interactive forms is more complex than a PDF with just headings, images, and text.

The general rule, though, is making PDFs accessible is more expensive than recreating the content as an accessible HTML web page.

Are PDFs accessible on mobile devices?

PDFs on a mobile device can be accessible, but many accessible features in PDFs don’t work on the most popular screen readers for iOS and Android. Plus, PDFs can be frustrating to read as you pinch to zoom in. Large PDFs can also download slowly on wireless data.

How do I create an accessible PDF?

Review WebAIM’s PDF Accessibility guide to learn how to create accessible PDFs.

Is having an accessible HTML web page version of an inaccessible PDF a viable solution?

Here are some questions to ask yourself when considering putting an HTML web page next to an inaccessible PDF as a solution:

- Would a user who needed an accessible version want to save the content in a PDF? If so, an HTML web page wouldn’t be an equivalent solution.

- Why is the PDF required to begin with? If you’re going to be making an HTML equivalent anyway, can the PDF be removed?

- Are the PDF and HTML web pages going to always be 100% equivalent in content? With a PDF and HTML web page, the content will need to be updated so it’s the same in both places.

PDF purge activity

You’re ready to improve your website’s accessibility by reviewing PDFs on your website. The accessibility result you’ll focus on is Link to PDF document.

Follow these steps to find and review PDF documents:

- Use the Canvas Accessibility Guide, Pope Tech Platform, or the free WAVE extension tool to find the Link to PDF alerts.

- Canvas Accessibility Guide – Test the syllabus, home page, and other pages for one course.

- Pope Tech Platform – From your Dashboard, drill down to the alternative text errors.

- WAVE extension tool (free) – Test four pages on a website or course you contribute to.

- Once you know where the PDFs are, review them to see if they are still necessary or convert them to HTML web pages. If you’d like to create a plan for this project, check out our PDF purge planning sheet (Excel).

Visit May Accessibility Focus: PDFs, non-HTML documents for more articles and video resources.